Over the past 30 years, one of the most dramatic — yet often overlooked — shifts in the U.S. economy has been the decline in youth labor force participation. In the 1990s, most American teenagers and young adults had at least some connection to work. Fast-forward to today, and far fewer do.

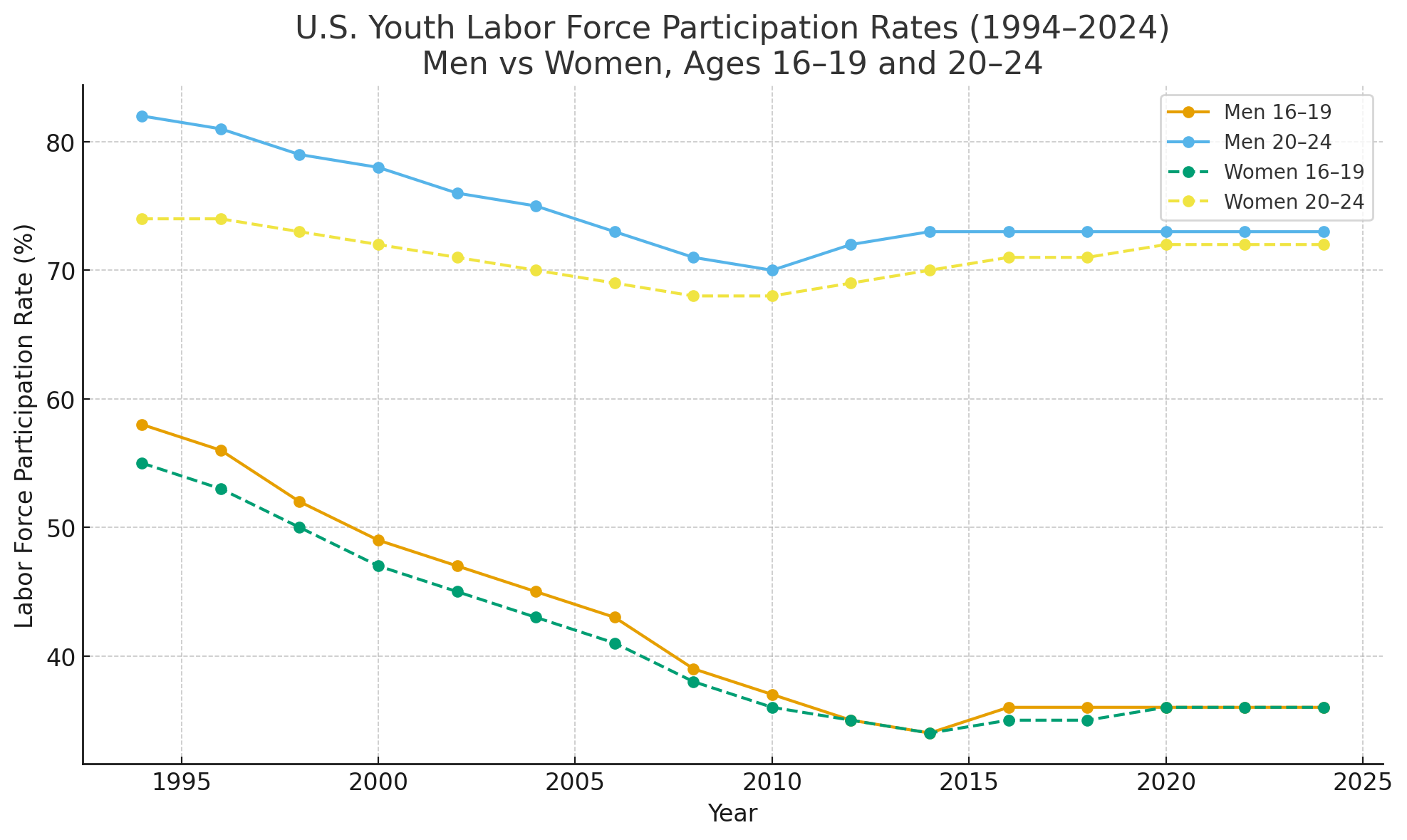

According to Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data, the labor force participation rate (LFPR) for men aged 16–19 dropped from around 58% in the mid-1990s to just 36% today. For men aged 20–24, participation fell from over 80% to the low 70s. Women show the same story, though slightly less pronounced: teen women’s participation fell from around 55% to 36%, and women aged 20–24 declined from about 74% to 72%.

The steepest declines came between the late 1990s and early 2010s, after which participation stabilized at much lower levels.

Why Did So Many Young People Stop Working?

Economists point to several structural and cultural forces reshaping the youth labor market:

- Schooling and Delayed Entry Into the Workforce

The single biggest factor is increased school enrollment. Over the past three decades, more teens and young adults have been staying in high school longer, attending college full-time, or taking summer classes. The 1990s and 2000s saw an explosion in post-secondary attendance and an expectation that education—not early work experience—was the ticket to success.

Even part-time or summer jobs have become less common as students focus on academics, internships, or volunteer experiences that align with future careers.

- A Shift in Job Availability and Wages

The types of jobs once popular among teens—like retail, fast food, and entry-level office roles—have declined or changed drastically. Automation, online shopping, and the gig economy reshaped entry-level work. Many employers now prefer older workers with experience or flexible schedules, leaving teens at a disadvantage.

Wage stagnation for low-skill jobs also discourages participation, as the economic payoff for early work experience has weakened compared to education.

- Changing Social Norms and Parental Expectations

Cultural changes also matter. Parents and schools increasingly emphasize academic performance, extracurriculars, and safety over work experience. The modern teen’s schedule is often filled with structured activities rather than after-school jobs.

Meanwhile, social and digital engagement — from gaming to content creation — provides alternative ways for young people to spend time and even earn income informally.

- The Pandemic’s Disruption and Partial Recovery

COVID-19 temporarily drove participation rates to record lows as service industries shut down. But the rebound since 2021 shows that many young people returned to work, though not enough to reverse decades of decline.

The stabilization seen since 2015 suggests a new equilibrium, where fewer young Americans work, but those who do often juggle school and part-time employment.

Why Participation Stabilized — and What’s Next

By the mid-2010s, participation rates stopped falling. Economists believe this plateau reflects two offsetting forces:

- On one hand, continued high education enrollment keeps many out of the labor market.

- On the other, rising living costs and student debt push some young adults back toward work earlier.

Another theory points to tight labor markets in the late 2010s and 2020s. As employers struggled to fill entry-level positions, they began hiring younger workers again, helping stabilize participation.

The Future of America’s Young Workforce

Looking ahead, most economists expect modest gains in participation among 20–24-year-olds as demographic pressures force employers to compete harder for labor. Teen rates, however, are likely to remain low.

Emerging factors could influence the next chapter:

- Hybrid education and remote work may allow students to balance school and part-time jobs more easily.

- Vocational and apprenticeship programs are making a comeback, potentially re-connecting young men to hands-on careers earlier.

- AI and automation could either reduce entry-level opportunities or create new, tech-assisted jobs for younger workers.

In short, America’s youth haven’t disappeared from the workforce — they’ve been re-routed. Education, technology, and cultural change have delayed their participation, not erased it. The challenge for policymakers and employers is to build pathways that reconnect young people to meaningful work before they reach their mid-twenties.